Storyboard artist and film director Lee Milby has a knack for turning so-called setbacks into opportunities. Her creativity, perseverance and sheer talent has accompanied her on a winding road that’s gone from fine art studio to the shoots of some of the world’s biggest brands.

As a woman, an adoptee and an Irish-Asian-American, Lee has firm ideas on how the industry needs to evolve to accommodate a broader spectrum of perspectives and working styles. Sister Motion sat down to soak up her story.

“No matter how Irish I am on the outside, everybody’s going to see me as Asian.”

What’s your cultural heritage?

I’m a transracial / interracial adoptee. I was born in Oahu, Hawaii, in the same hospital as Barack Obama. Biologically I’m mostly Vietnamese, and my parents started out as my foster parents. My dad is Irish-American and my grandmother had a full-on Irish accent. She’d bake Irish soda bread and give me a little vintage teacup of English Breakfast tea on her floral kitchen tablecloth. Her authentic Irishness was my first experience of culture outside of America. When I first moved to the city, friends were like, “Where are you from? What’s your background?” And I was like, “Oh I’m Irish.” What’s funny is they didn’t question it! That was the end of the conversation. That’s what I consider my heritage, but of course, no matter how Irish I am on the outside, everybody’s going to see me as Asian.

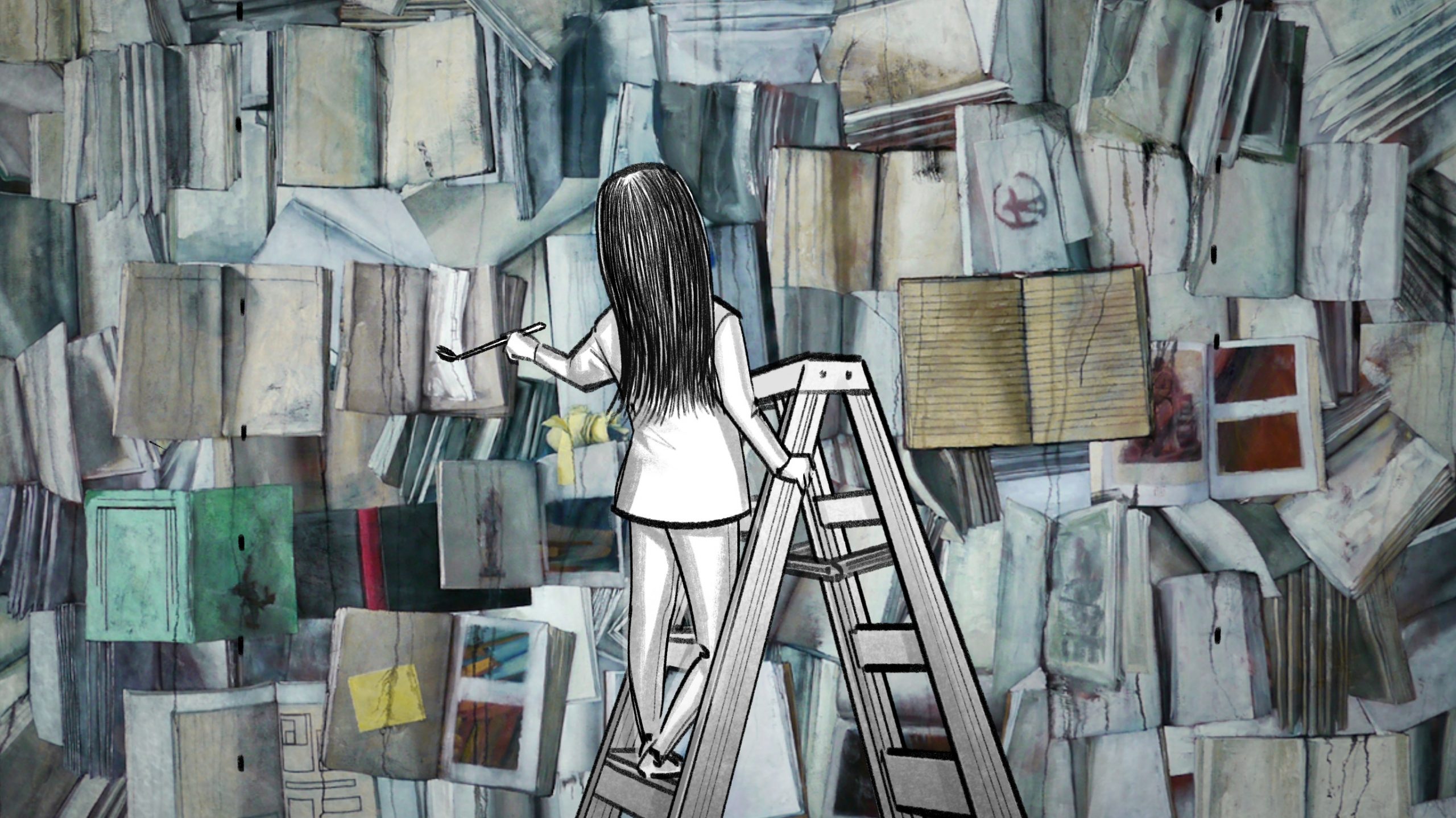

Lee grew up in an Irish family. Illustration Lee Milby.

You’re incredibly busy as a storyboard artist. How did your career unfold?

Storyboard art is like a subset of illustration, and I did do illustration in middle school and high school. But in fine art, illustration is a little bit vilified. It’s a purist thing. So when I declared my major as fine art painting, I said I was never going to do illustration because I was going to be a “serious artist”. When I do something, I throw myself full throttle into it. I did have some success – a solo show at Webster Hall, shows in some smaller galleries, a bunch of awards. But then I became allergic to oil paint! I developed this sensitivity to the materials, so when I’m exposed to it I have a reaction that prevents me from painting.

Apparently you weren’t going to let a little thing like a complete change of medium hold you back. What happened next?

I had a camera that I mostly used to document my paintings. I still wanted to be a part of the creative scene, so I got into event photography and video. I was shooting everything from bat mitzvahs to weddings, to raves and nightlife parties. I was shooting across the board just to try to stay afloat. I didn’t give myself time to mourn painting because it was all so chaotic and I was just trying to survive in the city. It was gig to gig and paycheque to paycheque.

That pursuit of the next gig is presumably what led you to film. What was your experience of breaking into the industry?

When I started getting into film sets with crews, I was often the only woman, aside from maybe the makeup artist if there was one. And I was often the only person of colour, so that was even more othering. I used to do a lot of hip hop music videos. I noticed that artists who were only used to working with other guys had a hard time viewing a woman as anything other than a dating prospect. Guys didn’t know how to talk to me! Also, I have a name with a masculine spelling. A lot of times I’d get an enquiry via the internet and people would think I’m a dude. We’d go back and forth planning a shoot, and then finally we’d get on a phone call and they’d think I was the secretary! They would change their whole demeanour. But it’s like, “You don’t have to do that! You don’t have to change up your whole communication style. We were having a normal conversation before! Can’t we just have a normal conversation now?”

How did you start directing?

I’d been working with this guy I was dating. He was a cinematographer and I always helped him on his projects – I was his right-hand woman. We co-directed a feature-length horror film together over a couple of years. After he submitted it to Cannes, he told me it got two out of three votes to be accepted, so we needed to make some changes for it to get in. Then he added at the end of the conversation that he’d removed my name from the project! My “revenge” was to direct a film project of my own, without his help at all. I realised that I didn’t need anyone else’s support or permission to direct films on my own. All I needed was my artistic vision! The rest is history.

Having finally achieved some success in film, you switched gears again. How did you evolve into a storyboard artist?

I had the skills to draw and paint, but that was in the background. I was doing art direction on a commercial but communicating with the director was getting difficult, so I was like, “Ok I’m just gonna draw it so you can see what the plan is.” I drew it and the client loved the boards. The gaffer saw my drawings and recommended me to work with Ben & Jerry’s on a project. And the director for that first project asked me to storyboard a commercial for the NAACP featuring John Legend.

“The whole time I was like, “Wait, I’m supposed to be a director, a filmmaker – I shouldn’t be doing this drawing stuff!” But the jobs just kept coming.“

How did you go about getting representation?

I had a lot of self-doubt from bad experiences trying to make it as a filmmaker, so when it came to storyboarding I didn’t have a lot of confidence. On a whim, I called the biggest storyboard artist agency in the United States. The woman who answered told me to send my portfolio, but she also said, “Just so you know, we get many portfolios a day and we really don’t accept that many.” I sent it and a couple of hours later I got an email from the vice president of the company that said, “Can we get on a phone call? We’re very interested in you.” It threw me for a loop. But then after that I had an agent!

Is it common to find a woman working as a storyboard artist?

I’m very much in the minority. A lot of storyboard artists enter not from the film world, but from comic books – which is a very bro dude world. I think there’s a historical reason, too. All the veterans are men. As a storyboard artist, you connect with a director – if the director likes your style, your workflow and your personality then you continue with that director. Having experience as a director myself certainly helps. Knowing the lingo, the equipment, cameras, lenses – all of that certainly helps to communicate when translating the director’s vision to 2D.

Do you feel like the world of filmmaking is improving for women?

Definitely. It’s better from when I first entered the industry, only being seen as a sex object and being called a babe or sweetheart on set. Now post-me-too movement, these conflicts have entered the zeitgeist. We can have an open conversation rather than in the shadows. It went from this “women’s issue” to become an industry issue. That was a huge reframing that’s sparked a lot of positive change. I think the roots of that issue are still for sure there. But I think that moving forward the biggest thing we can do is keep creating safe spaces, keep creating projects for women, people of colour and other marginalised groups so we can flourish without worrying about the tyranny of these oppressive elements that have prevented us from being creative, wonderful, artistic people!

What needs to happen for us as a society to get there?

Having spaces where women can flourish and feel safe. I had one shoot where it was all women except one male – and he got replaced halfway through by a woman. It was a 20-person crew and it was a wonderful experience. I think in spaces where it’s all-female energy, there’s a calmness. There’s not that militaristic, aggressive environment that a more masculine film shoot has. There’s a lot more support and communication about how to fix problems instead of throwing ego around and pressuring people to find solutions on their own. No one was made to feel like they weren’t measuring up – it wasn’t a competition, it was a team effort. There was one slightly tense moment where we were trying to get this thing done, and the producer burned some sage and was wafting it around. And it really calmed everything down! It was a great experience and more of that needs to happen.

What does the future of filmmaking look like for you?

I think as more women are in positions of power – specifically hiring power – we can weed out the people who can’t work with women.

It’s not going to be acceptable anymore to say, “I can’t work with a woman director.” If you can’t work with a woman, you’re not going to work at all!

Lee Milby is just one of many talented women in the Sister Motion talent collective.

To connect with Lee on Instagram click @leemilby